Asymptotic notation

Asymptotic notation characterizes the limiting behavior of a function based on its growth rate. It allows for algorithms to be classified according to how their runtime grows as a function of input size, essentially serving as a measure of time complexity; how efficient an algorithm is with time.

Big \(O\)

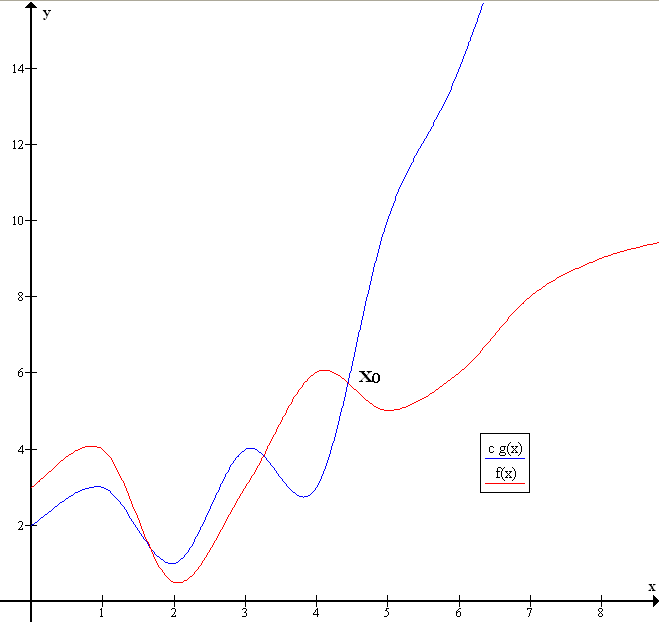

Big \(O\) notation describes the asymptotic upper bound of a function. If a function is "Oh of" some other function, then for sufficiently large inputs, it will always be below that other function.

Basically, \(f \in O(g)\) if \(f\) is always bounded from above by \(g\) multiplied by some positive constant \(c\) after \(n\) exceeds \(n_0.\)

To prove Big \(O\), all you need to do is find a single witness \((c, n_0)\) that fulfills the above definition.

If \(p\) is a degree-\(k\) polynomial function, to quickly prove \(p(n) \in O(n^k)\), try \(n_0 = 1\), and set \(c\) equal to the sum of all positive coefficients and constants in \(p(n).\) That combination is guaranteed to work as a witness.

To disprove Big \(O\), you need to show that for all \(c \in \mathbb{R}^{+}\) and \(n_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{+}\), there exists \(n \geq n_0\) such that \(f(n) \gt c * g(n).\) In other words, no matter what witness \((c, n_0)\) you select, there's always going to be some eventual \(n \geq n_0\) that allows \(f(n)\) to exceed \(c * g(n)\), which disqualifies \(g(n)\) from being an upper bound of \(f(n).\) A proof by contradiction will get the job done. Assume there is a witness that fits the definition of Big \(O.\) Then, show how this forces \(n\) to have an upper bound, which is absurd.

Big \(\Omega\)

Big \(\Omega\) notation describes the asymptotic lower bound of a function. If a function is "Omega of" some other function, then for sufficiently large inputs, it will always be above that other function.

As you can imagine, proving and disproving Big \(\Omega\) is structurally identical to proving and disproving Big \(O.\)

What's more interesting is the connection between Big \(O\) and Big \(\Omega\), and how proving one effectively proves the other, but with the roles of the functions swapped.

Recall that when two statements are connected by a biconditional, they are logically equivalent to each other.

Big \(\Theta\)

Big \(\Theta\) notation describes the asymptotic average bound of a function. If a function is "Theta of" some other function, it said to be "on the order of" that function, and for sufficiently large inputs, their growth rates will roughly match.

Proving Big \(\Theta\) requires proving both Big \(O\) and Big \(\Omega.\)

Here's some shortcuts, but remember they don't serve as proofs:

- If \(p\) is a degree-\(k\) polynomial function, \(p(n) \in \Theta(n^k).\)

- If \(g\) is a base-\(b\) logarithmic function where \(b \gt 1\), \(g(n) \in \Theta(\log n).\)

However, you can't discard the bases of exponential functions! They're important.